WHO definition of health appears too static

WHO definition of health appears too static

At the time, there were already voices saying that the 1948 definition of the World Health Organization (WHO) was too static and ambitious for the current age. The definition was formulated in 1948 and reads: ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’ What WHO had not taken into account was that this definition is also a demarcation: If you do not fit the description, you are not healthy.

It was also impossible to foresee, at that time, how our health would develop. In those days, we were mainly dealing with infectious diseases, which we ‘cured’ using antibiotics. We had no inkling that, decades later, we would face mainly chronic diseases. The WHO definition means that, in the current era, a large portion of the population is declared unhealthy. Without this being the intention, the way the definition was formulated has led to strong medicalisation and every possibility of treatment is being deployed in order to meet the definition of health.

Need for a dynamic concept

Since the WHO formulated its definition of health, people have been looking into it. When physician and researcher Machteld Huber herself fell ill, she noticed that she was able to greatly influence her own recovery. This led her to organise an international conference in 2009, together with the Health Council of the Netherlands and ZonMw (Netherlands organisation for health research and development). Numerous experts from all over the world worked on the definition of health. Their insights led to the new concept: Health as the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges.

Elaborating the concept

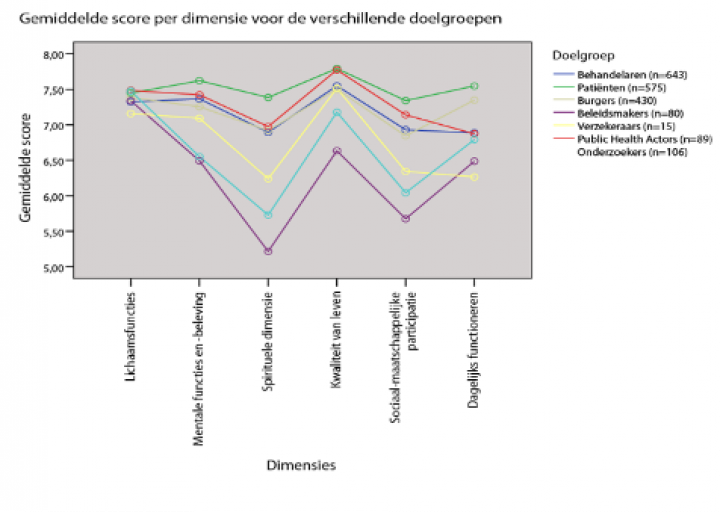

Huber then presented the concept to 140 patients, physicians, policymakers, citizens, health promoters, researchers and insurance companies. They were asked what they would look for when assessing whether someone is healthy. This yielded no fewer than 566 health indicators. Huber reduced these 566 indicators to form a core of 6 dimensions of health. These were then again presented for feedback, but this time to almost 2,000 representatives of these groups.

This essentially resulted in very different views on the value of each dimension of health. For example, care professionals, especially physicians, and policymakers appeared to attach great importance to bodily functions in relation to symptoms and physical condition, whereas patients themselves consider all dimensions to be important, including quality of life and meaningfulness. See the figure below.

By emphasising resilience and self-determination, patients feel that their strength is what matters, as well as their ailment. Huber chose this view of patients as a starting point, called the elaborated concept Positive Health — which could be visually presented by using the spider web and enabled working with Positive Health.

The big difference with the WHO definition is that Positive Health does not see health as a goal or end point. Instead, it places people’s capabilities such as resilience and self-determination in a central position, so that development always remains possible.

In 2011, the British Medical Journal published on the new dynamic concept of health by Machteld Huber and others. An article titled ‘How should we define health?’ made it to the cover of the leading medical journal. In 2014, Huber obtained her doctorate on the concept of Positive Health.